Part One

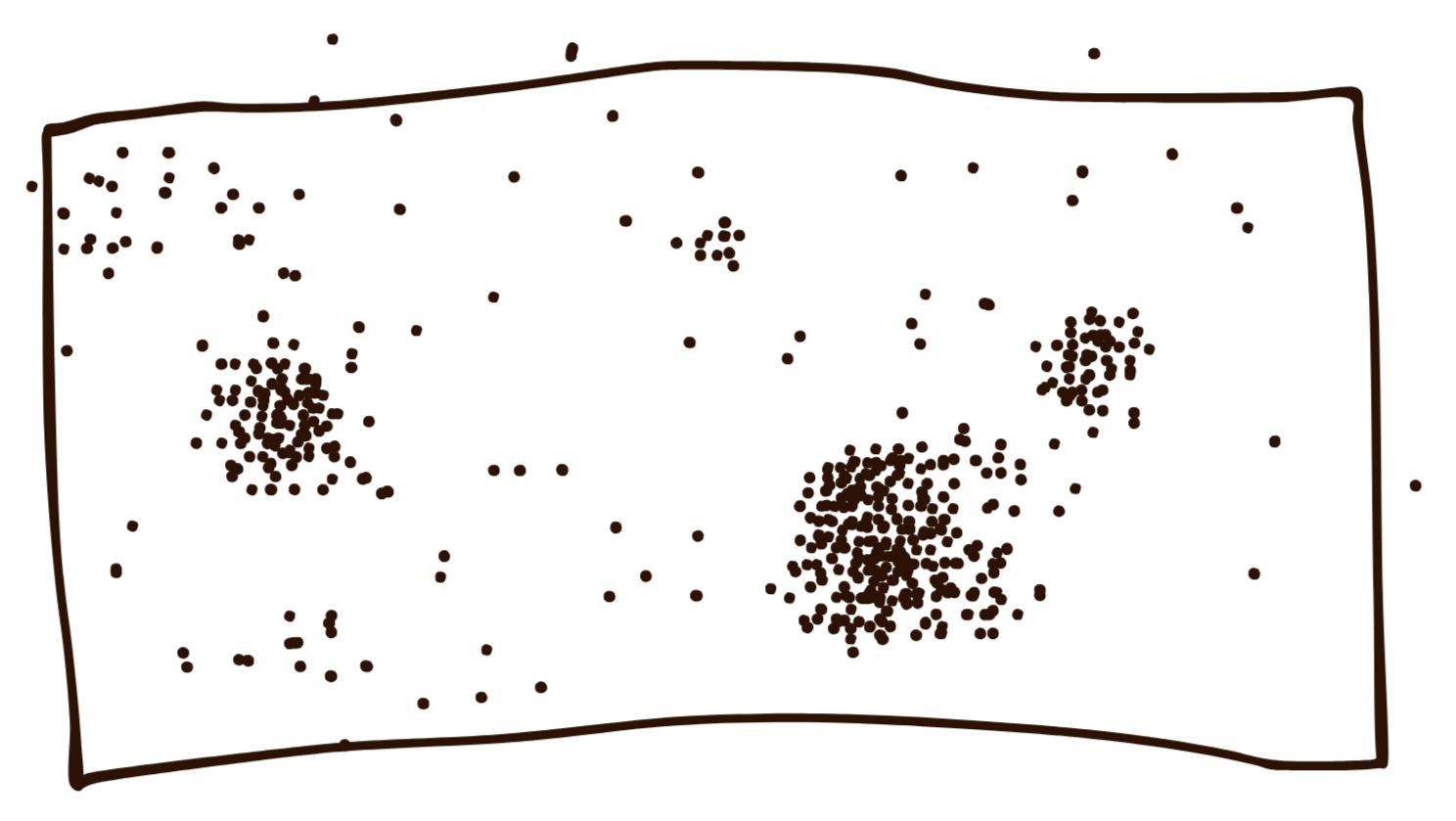

If two graphs existed to compare the structures of a weekday vs. a weekend, they might look something like this:

A. The Weekday

B. The Weekend

The weekend has an offer that allows us to explore the fringes while recovering from burnout. We probe a house key into a baggie, we let the stranger buy us a drink, we place the square under our tongues.

We dance.

A romance exists on the dancefloor. We feel like we are far, far away (the transcendent experience that relieves us from thought) and we feel that we are very near (the connection to our bodies, our feet on the floor, the people in the room, the sweat and smoke, and the beat).

On weekdays, the structure is laid out clearly for us. We abide consciously and subconsciously to a pattern dictated by our economic system. Staying inside of the lines is easy, as exploring the fringes requires a creative thinking that is not compatible with burnout.

On the weekends however, the structure becomes ambiguous.

Work? Sleep? Play?

We do all three or we do none.

two

Yet it stands as an illustration for aliveness itself.

A beat is intrinsic, we cannot help but tapping our foot or clapping along to it. The beat drives our foot to move, to keep up with it, to synchronise, to collaborate.

The foot makes contact with the earth, grounding us. It is the first part of the body to awaken to sound, responding instinctively to the pulse of aliveness itself.

A beat– minuscule, insignificant, almost nothing, is as fundamental to life as the first unicellular organism is as fundamental to the universe.

Change the beat and the whole structure collapses.

It stands in the centre, allowing life to unfold around it.

If a graph existed to display the increase in techno listeners in recent years, it might look something like this:

three

techno listeners

bad events in the world

What do we hope for as a culture when we are hopeless and there is no God to save us?

Perhaps we hope that culture will change structurally. In the meantime, we accept a compromise.

We work all week in the current structure and change ourselves, our brains, our culture structurally on the weekends.

The sound of a musical beat began with the hands, clapping or knocking rocks together to produce a sensation akin to our primal metronome.

four

Out with the band, in with the DJ.

The technology used to create modern techno music is oxymoronically our generation’s way of connecting with the original source of all music.

Today in Australia, the intrinsic urge to recreate this sensation has exploded. So much so, that avoiding music with a repetitive beat is futile. Australians listen to more electronic dance music than any other country.1

Growing up, I believed that God did not watch over Australia. God was something foreign, for landlocked countries that did not have the ocean or ancient countries that did not have TV.

Discussions of religion and politics were encouraged at the dinner table, so long as they were being criticised.

God was explained to me as a by-product of brainwashing, an imaginary friend that naïve and delusional adults convinced themselves to keep around for company. God’s forgiveness and lack of judgement was a clever way for paedophile priests to justify their inexorable actions. God was always linked to religion, and religion caused wars.

In the first year of COVID-19 lockdowns, my families deeply instilled atheist opacity began to corrode.

Those that have a spiritual practice will thrive, and those that don’t will suffer, a friend told me over the phone. In fear of being amongst this group of sufferers, I started to follow guided hypnosis meditations every evening.

One evening in my bedroom, on my floor lying down, I was following a guided hypnosis. Deep into the experience, I felt a steady but gentle pressure on my shoulders. A feeling, no, a knowing, that I was not alone in my bedroom but unconditionally supported by something ineffable yet encompassing.

So that’s what God is,

I remember thinking when I woke, my pillow wet with tears.

five

six

Bettina E. Schmidt, a professor at the Centre for Humanities and Social Sciences (University of Wales), conducted two surveys during global lockdowns on ‘The Fruits of Spiritual Experiences During the Pandemic’.

One person responded to the survey stating:

I feel very ‘inwards’ and do not really wish to engage in other things. I also feel as though I have my full religious experience within me at all times so there is no need to ‘go’ elsewhere.2

This is how I spent the rest of lockdown, in a state of inwardness, feverish to have another taste of this alternative, more complex existence.

I always felt that the description our world prescribed to God was too concrete to convince me. If there was a higher power, I figured its form would not abide to earth’s material guidelines, making an illustration untranslatable.

What is God then?

An alien?

A cavernous abyss?

A feeling?

seven

In countries where God is watching over, the temple is a place to share all the love inside us. In a country without God, like Australia, we go to a bar, club or doof perhaps to get inebriated, but moreover, we go to engage in a unification with our peers, a dissolving of territorial boundaries.

eight

In Tao Lin’s essay, My Spiritual Evolution, he says, “Trying to convert the [spiritual] experience into a language made for another world… distorts and obscures the already muzzy memory of what happened”3.

Trying to explain what happened on a dancefloor is like trying to make sense of a pig’s grunts or make meaning from the pattern of dried leaves on the ground. It is the very moment void of thought or meaning-making that produces the experience that lasts– the one that sticks even on a weekday.

The dancefloor, in that brief period where Melbourne opened again, was where my relationship with God integrated.

nine

The individual territories imposed on us as we came of age in COVID lockdowns dissolve. Now we slobber and sweat on each other, engaging in a unification that answers the deep ringing of ancient church bells within us. The bells of a village, the bells of a community.

This temple is a place where the love we have for each other is cracked open like a glowstick in the night. The temple is where the inner experience is free to be expressed and released, is free to be shaken out of the body, unlike in the work week, where we maintain a permanent social distancing, not as severe as COVID, but enough to hollow out a place in us where community should reside.

“I’ve never experienced a place where I could truly share all the love that’s inside me,” writes a user on the subreddit r/aves.4

If the rave, the bar, the nightclub is a temple,

then the dancefloor is communion.

Does recreation become less important as we age,

or more important?

PLUR is the acronym of the rave community’s ethos:

Peace, Love, Unity, Respect.

If the work week had an ethos in effect also, its acronym might be something like COPE:

Compliance, Obligation, Powerlessness, Enforcement.

But a weekday does not have an ethos, only a KPI.

ten

references

- Colquhoun, J. (2024, October 17). Stats reveal that Australians listen to dance music more than any other country. Mixmag Australia.

- Schmidt, B. E., & Stockly, K. (2023). The Fruits of Spiritual Experiences during the Pandemic: COVID-19 and the Effects of Non-Ordinary Experiences. Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society.

- Lin, T. (2024, October 30). My Spiritual Evolution. Granta.

- u/sirshredsalot666. (2023). My first rave was a life-changing experience [Online forum post]. Reddit.